It’s My Party (and I’ll Cry about Butthole Pain if I Want To)

A guest post about endometriosis, or what it’s like to be a woman navigating a world that doesn’t care about women’s pain.

Hey check it out—it’s Healings’ first guest post! Sabina Formanek is a writer and wine expert who recently left LA for Vermont and started listening to too much Phish. We try not to hold either of those life choices against her though. Enjoy!—Garrett

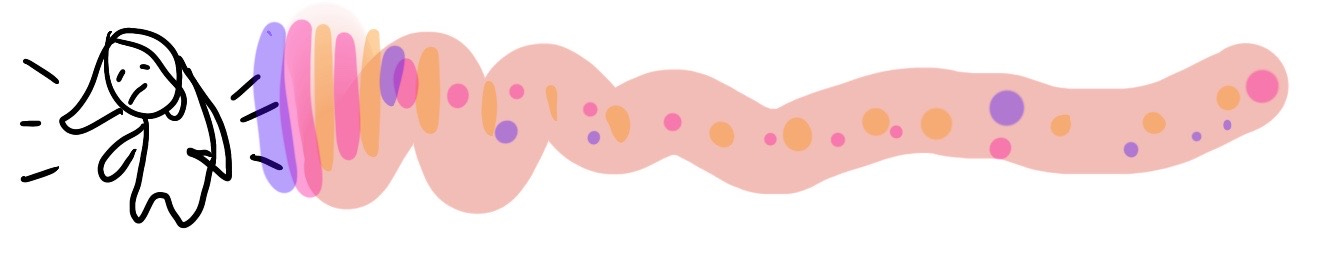

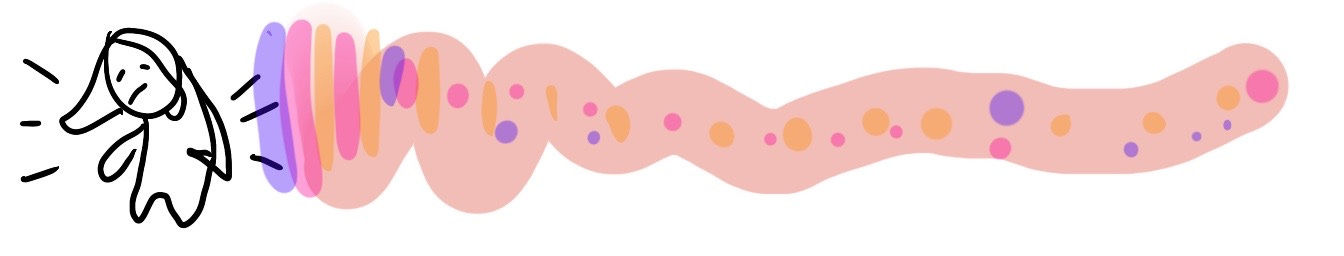

Endometriosis is a disease where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows elsewhere in the body. The function of the uterus and its lining (the endometrium) is: baby house. Hormones signal to the tissue when it’s time to build the foundation, and if no one gets knocked up that month, the house gets discarded—et voila, menstruation. With endometriosis, the ectopic tissue reacts to those same hormonal signals, but instead of being discarded every 28 days, it sticks around, resulting in internal bleeding, inflammation, and lesions.

The symptoms one feels when they have endometriosis vary from patient to patient. Each body responds differently to inflammation, and depending on the location of the lesions, the disease can be found on almost any organ. The inflammation also triggers the body to create scar tissue and adhesions, which then can cause further discomfort, in some cases causing organs to adhere to one another.

Endometriosis patients frequently report fatigue, extreme bloating, heavy bleeding, irregular periods, difficulty getting pregnant, and nausea, among other symptoms, all of which can be captured in a single word: pain. But pain is abstract and subjective, and a growing body of research suggests that women’s pain is historically more likely to be misinterpreted or downright ignored compared to pain experienced by men. This is especially true when it comes to women’s reproductive health. With endometriosis, the pain can sometimes be acute, but it can also be more generalized. Many people report pelvic or abdominal pain, and that can radiate to your hips, legs, and back. What this all adds up to is a situation where, on average, it can take up to seven to nine years for endometriosis patients to finally receive a diagnosis.

Because pain is so subjective, it can be hard to know when it’s signaling something serious, especially when you’re someone who’s used to having their pain diminished, i.e. a woman. When my pain set in during the spring of 2022, I initially dismissed it. I had relocated back to my home state of Vermont from Southern California, and was excited to live rent-free for a while and spend more quality time with my family. I got a sales position with a wine distributor, and drove all over the state visiting shops and restaurants. For a while, I thought my nagging low back soreness was from driving around in the flimsy seats of a Toyota Prius. I figured I should exercise and stretch more, work on my posture. When I started to experience bloating so intense it threatened to pop the button off my jeans, I assumed it had to be a sensitivity to something I was eating, or that my digestion was sluggish because I was lazy. But eventually, the pain got so bad it’d wake me up at 3am with a deep ache through my entire abdomen. On those nights, I’d sit in the bathroom through waves of nausea, my head pressed against cold tiles. I even vomited a few times, and historically I am not a puker. At what point does a strange and growing ache behind your butthole become an emergency?

I got my answer on a Monday morning while getting ready for work, when a piercing pain shot through the middle of my belly. The urgent care in town was about ten minutes away, and I remember gripping the handles of the car as my mom drove us, trying my best to take deep, slow breaths. At the urgent care, the first thing they did was take a urine sample to determine whether I was pregnant, because apparently that’s the easiest way to explain vague symptoms in the middle body zone. Then, following an ultrasound, I was sent to a urologist’s office forty-five minutes away in order to rule out kidney stones. At the urologist’s office, I was given another ultrasound, then a catheter to drain my bladder. After that, a doctor came in, put a cystoscope inside of me, and told me my bladder tissue was healthy. I was sent home from that appointment with no more information than I started with, replaying the traumatic sensations in my body, the source of my pain still a mystery. It seemed the doctors’ primary concern was ruling out any condition that could have threatened my life, and the only advice I was given was to follow up with a gynecologist. I slept away the rest of the day, the pain dulling bit by bit until it was just an intense muscle soreness across my entire belly, similar to if you’ve been conned into a pilates reformer class by a super-fit friend.

The only upside of this incident is that it prompted me to make an appointment with a new doctor, which is how I met my OB-GYN, Dr. Cotter. A petite woman whose delicate mannerisms and kind face reminded me of my grandmother, she pointed to my ultrasound images and told me my uterus was healthy, as was my right ovary and fallopian tubes. The problem, however, was that my left ovary was as large as a softball (a normal ovary is about the size of a walnut). She suspected endometriosis right away, and let me know that I would need surgery to treat it. She then took my hands in hers, looked me in the eye, and told me it was not normal or ok to wake up in the middle of the night because of pain. Upon hearing these words, a wave of validation crashed through my body.

Endometriosis affects 10-15% of reproductive-age women. Despite its prevalence, it’s common for patients to have to see multiple doctors, and to have their pain minimized or written off. Physicians will label you as dramatic, anxious, or “hysterical,” and suggest mental health treatment and over-the-counter pain meds. If a doctor does suspect endometriosis, they may recommend hormonal birth control to suppress your symptoms. Most endometriosis patients have some form of horror story of having been mistreated by a medical professional. It’s exhausting to be in pain without a known cause, but to then be gaslit about the way you feel in your own body is devastating.

My first surgery took place the day before my 32nd birthday. As I was wheeled into the operating room, Dr. Cotter held my hand once again as the drugs put me to sleep. The next time I opened my eyes, I was in post-op with an ice pack slung across my midsection and a radiant nurse offering me ginger ale when all I was interested in was asking her about her skincare routine. Dr. Cotter explained that everything went great—she didn’t find disease outside of the endometrioma, just some minor scar tissue but no major endometriosis lesions. Without a definitive cure, however, I would need repeat periodic surgeries to manage the disease, and be on the rinse and repeat schedule like many other endometriosis patients. I got dressed in my soft clothes and slipped on my birkenstocks, and my mom drove me home with a pillow between my belly and the seatbelt. I spent the next week recovering, thinking to myself, I could do this once a year, if I had to.

In the spring of this year (or a time we call “mud season” in Vermont) I signed on to open a wine and speciality shop in White River Junction. The team was just me and the owner, and we spent two months staining shelves, sourcing antiques, ordering wines, assembling furniture, and crying about wallpaper. OK, it was just me crying about wallpaper. I was dealing with increased pain and fatigue, but I attributed it to the long days of physically and mentally exhausting tasks. Even as the pain got worse, developing into a deep ache in my core, I continued to play it down. I could still participate in life, I rationalized, the pain riding shotgun alongside me.

Eventually, I went in for a physical with a primary care doctor, someone who’d come highly recommended. When I mentioned my symptoms of back pain, abdominal pain, and fatigue, I also told her about my history with endometriosis. Armed with all of that information, the doctor suggested my recent symptoms could be…constipation. I responded by telling her I had normal and regular bowel movements, enjoyed and frequently ate foods rich in fiber, and took an expensive (and awesome) probiotic every day. She responded by saying, “Well you could be backed up way back there and you just don’t know it.” I sat there in silence, blinking, fairly certain I was not the one full of shit. Thankfully, I also had an appointment to see Dr. Cotter the next week.

While I’d known my condition was chronic, I wasn’t expecting what came next. Even though I was only five months out from my first surgery, Dr. Cotter explained during our appointment that the endometrioma had grown all the way back, and was about to surpass the previous growth in size. My options this time were to have the same procedure, removing the growth but retaining my ovary, or to remove the ovary entirely. Dr. Cotter talked me through both options, with the obvious downside of the former being the chance of the endometrioma growing back once again. The downside of the latter was it would take whatever follicles (future babies) I had, and instantly reduce that number by half.

To contemplate compromising your future fertility at a time where you haven’t even made up your mind about kids is a bizarre feeling, like a quiet alarm in the distance. The ideal scenario would be my right ovary picking up the slack, ovulating normally when I’d like it to. But in the back of my mind I wondered, What if that squishy walnut is just for show, and doesn’t function at all? That still wouldn’t make pregnancy or childbearing impossible, but as a person who wildly romanticizes every morsel of life, it made me sad. I selfishly wanted my future imaginary offspring to be born without expensive, clinical, and painful intervention.

Ultimately, I decided to yeet the left ovary, not wanting to risk the endometrioma making yet another appearance. I was going to have George Michael-style faith in the right ovary, should I ever want it to be put to use. The second surgery felt like old hat, and I joked in pre-op with Dr. Cotter that I was literally putting all of my eggs in one basket. That killed with her and I’m sure she performed surgery extra-good that day because I was her most hilarious and clever patient of all time.

In reviewing my surgery with me, Dr. Cotter let me know that my ovary with the endometrioma had grown quite large, resulting in scar tissue through the entire left side of my abdomen and hip area, which is why this operation took much longer than the first. Scar tissue had to be removed from my large intestine, bladder, and areas near my ureter, or what connects my kidneys to my bladder, aka the pee-pee super highway. Despite all that internal action, because of the marvel of minimally invasive surgery, my damage is just three small scars and a daily dose of synthetic progesterone to suppress ovulation. Moving forward, I’ll have yearly ultrasounds, and if they show anything growing I will have surgery once again to manage the disease.

Endometriosis is chronic and incurable. It won’t lead to death, but it’s a lifelong condition. I feel empowered, having received a diagnosis, treatment, and a game plan for the future, but not all endometriosis patients are as fortunate. Many of us can go years, even decades, without receiving a diagnosis or effective treatment, our pain minimized, our experiences discounted. Those moments when I felt like I was heard and seen—when a doctor held my hands, and listened, and understood my pain with compassion and empathy—are the ones during which I felt the most relief through this entire ordeal. Perhaps if we didn’t throw so much money at boner pill research, more women could experience something similar.

This is the Healings Newsletter. It’s sent out on Thursdays.

It’s written by Garrett Kamps and edited by Tommy Craggs.

It’s illustrated by Abner Clouseau, whose pen name we apologize for.

It’s about illness and recovery, and comes with jokes.

Healings is free for all, but if you subscribe, half of every dollar goes to charity, currently the Patient Advocate Foundation. The other half goes toward paying our contributors. This is the model for now. We reserve the right to adjust it but will let you know if we do.

“Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” — Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor