Marty Anderson Is Okay

What follows is a cover story I wrote for SF Weekly that was originally published on March 3, 2005. That paper has since been sold and re-sold countless times, and its online archives are a mess (to the extent they exist at all), plus they treated all us employees like shit. Hence, I’m reclaiming this piece for my own purposes. Enjoy.

Marty Anderson Is Okay

The Cluttered House in Fremont

Marty Anderson lives in a one-story house in Fremont with his mom and dad. As you walk through the front door and step on the brown, squishy carpet, the first thing you notice is the charming amount of clutter. Every wall is covered with pictures and drawings and photos, framed and unframed, hung, taped, or simply tacked up. On every surface is a bauble or a doodad: tiny ceramic horses, half-burnt candles, vinyl records with Mighty Mouse on the cover. Someone has drawn a picture and hung it up next to the painting of a Hindu god I can't identify. The picture says, “You were supposed to read this right now.”

Sitting, standing, and lounging amidst the jumble are the majority of the members of a band called Okay. They are: Ian Pelucci, bassist, prone to smiling, relaxed on the couch; Jay Pelucci, drummer and Ian's brother, who closes his eyes and wears no shoes while he plays; Yosef Lewis, guitarist, yoga practitioner, and the only bearded member of the group; Anna Weisman, who plays the autoharp, has big brown eyes, and is engaged to be married to the aforementioned Lewis; Amanda Panda, percussionist, who does, in fact, have the cute, rounded features of a panda; and Anderson, Okay's chief songwriter, who sits behind his Juno-106 synthesizer and Wurlitzer piano wearing what I will come to understand is his trademark fluorescent orange beanie, as well as layers of flowing blue shirts, colored, fuzzy wristbands, black beads, thick white spectacles, and a pair of sky-blue hospital pants with “Kaiser Permanente” printed on them.

“I want everyone to bring bells,” Anderson says to the musicians, who are packing their instruments for what is to be Okay's second-ever show the following night. “That's why I handed out the special sock.”

The bells in question are each member's set of Tibetan Tingshas, which, according to one Web site, “create sounds to calm the mind and induce deep relaxation.” The Tingshas are played at the beginning of an Okay performance to establish what is most definitely and appropriately a spiritual tone. The special sock is, as far as I can tell, not that special.

“Does everyone have a party favor, a gun, and one of these?” asks Anderson, holding up what looks like a miniature kazoo.

“Bang!” Panda fires her weapon, a toy cap gun, but is instructed to stop because ammo is scarce. The gun is packed up, as are the drums and the guitars and the bass, the autoharp, Panda's two dozen percussion instruments, the kazoos, the things that look like kazoos, the Casio, the melodica, the countless effects pedals that Anderson hooks up to his keyboard and to his voice, the ironing board that Panda uses as a music stand, the mini-xylophone for Jay Pelucci, the special chair that the 27-year-old Anderson has to sit in, the amps, the amps, and the amps.

Pretty soon the band members will have left Anderson's place and headed back to their apartments in Oakland. Anderson, who's also wearing big, furry slippers the size of footballs, will hug and squeeze them all, and then begin packing wires and pedals as we sit in his only slightly less empty living room talking about everything surrounding Okay's debut on March 29 of High Road and Low Road, two separate discs culled from the same sessions, and the first major release of any Anderson-penned material since his former band, Dilute, put out the mighty magnum opus Grape Blueprints Pour Spinach Olive Grape in 2002.

Anderson will explain that he recorded these songs during a tumultuous time in which he was living with his then-girlfriend, Anna Weisman, who was also sort of in love with Yosef Lewis, with whom Anderson, at the time, did not get along. There was also Anderson's disease, named after a doctor called Crohn, which, for those who don't know (I didn't), is “an inflammatory bowel disease … that causes persistent or recurring inflammation of one or more parts of the intestine,” or, to put it another way, is a really fucked-up digestive disorder that makes you shit blood and that has been known to push the 5-foot-8-ish Anderson down to 90 pounds of taut skin and bones. So there was the disease and the apartment in Oakland and a corrosive love triangle, and out of this fertile shit-pile grew the magical psychedelic pop of Okay, which transforms — rather alchemically, via sugary melodies, warm baths of keyboards, jaunty rhythms, and all the kazoos you can take in — this thick, weighty sadness into a joyful celebration.

Anderson is about to tell me all of this, but first I take him up on his offer of a Bud Light. I open the fridge, one of two in his quaint, '50s-style kitchen, and grab a cold one, noticing, among the beer and eggs and veggies, the plastic bags upon plastic bags of white, milky liquid stacked on top of one another. The solution in the bags is called TPN, and it flows through an IV and into Anderson for 16 hours a day, every day. It more or less keeps him alive, and has for the past 10 months.

An E-Mail Exchange That Describes the Facts Surrounding the Illness

Kamps: Dear Marty, could you please describe your medical regimen and the various drugs you take?

Anderson: My medical regimen? Um … Currently I am on Pentasa, Flagyl, Prednisone every day. Morphine, Vicodin, Valium are when I need them, but keep in mind I've been on pain killers off and on — mostly on (at least to some degree) — for 6 years now, so it takes quite a bit to get an actual “relief” effect on this type of physical pain. T.P.N. is the white bags, the lipids (fats) are what make it white. It's an acronym. But I forget what the P stands for. Total, (something), Nutrition.

I see my docs about once every few months. I go in weekly to have my PIC line and my dressing changed (that is what is in my arm: the IV PIC line is a small plastic tube that I wrap around my wrist, and the other end goes in my arm, into my vein, up around my shoulder, and directly into my heart. Infection is the biggest danger. No protection. But I am careful). I also have the IV site cleaned and caps replaced weekly etc. So I have that pick line coming out of my arm 24/7. That is where they draw the blood too. They do that every week as well. 3 vials! I've been meaning to ask if they could take blood work every two weeks. I don't want my hemoglobin going way down again. I need my blood! [page]

Garrett, to be honest, I'm a little weirded out by telling the world I take all these poisons. Do you really HAVE to put this in? I guess it doesn't matter. I mean, it's the truth. So I don't really care I guess. I just feel strange and don't really think it's necessary.

The Short History of a Great Band

It is important to understand that this is not a story about a sick person having an epiphany on his deathbed, although it does include that. And it's not a story about a bizarre love triangle, although that, too, factors in. This is a story about Great Music.

I knew nothing about Marty Anderson when I discovered Dilute in 2002. The act's first record was called The Gypsy Valentine Curve, but the one my friend told me about was its second, far superior album, Grape Blueprints, so I picked that up and proceeded to have my brain sucked out of my head through my ears. Dilute was a four-piece comprising Anderson (then on guitar), the brothers Pelucci, and Craig Colla. Its sound on Blueprints is best likened to a firefly caught in a jelly jar: bright, frantic, always trying to break out of something it doesn't know the dimensions of, resting in some moments, going crazy in others. Dilute's music lured the listener in with sweet, finespun guitar lines, delayed and effected and woven into swaying rhythms, the whole thing a walk in the park until a thunderclap detonated and it started pouring distorted torrents of guitar noise and cymbal slaps and big chunks of bass. It was like weather, beautiful and destructive, and when it settled down the clouds would part and there'd be a song like “Explosion,” which is two bright guitar lines dancing kitelike around each other as Anderson sings, in his puckish warble, “So bright/ Ooooohhhhhh/ So briiiighhhhht/ Ooooohhhhhh.” Then the clouds would gather again for the 26-minute-plus “0 vs. 1.”

Like I said, I didn't know squat about Anderson or his illness back then, just that I thought he was among the best guitar players in the whole wide world of indie rock, leading one of the genre's best-kept secrets. That was enough to make me want to pursue a story. But at that point I was already too late.

A Foreboding Exchange Via E-Mail With Jay Pelucci, Dated March 4, 2003

Hey Garrett,

Dilute doesn't have any shows lined up currently. We were offered a show with Pinback, but we couldn't do it due to health problems with a band member. Very big bummer. If by some miracle we are able to play a show in the near future, I'll let you know …

Take care,

Jay

The Pain in Marty's Spine Is What Saved Him

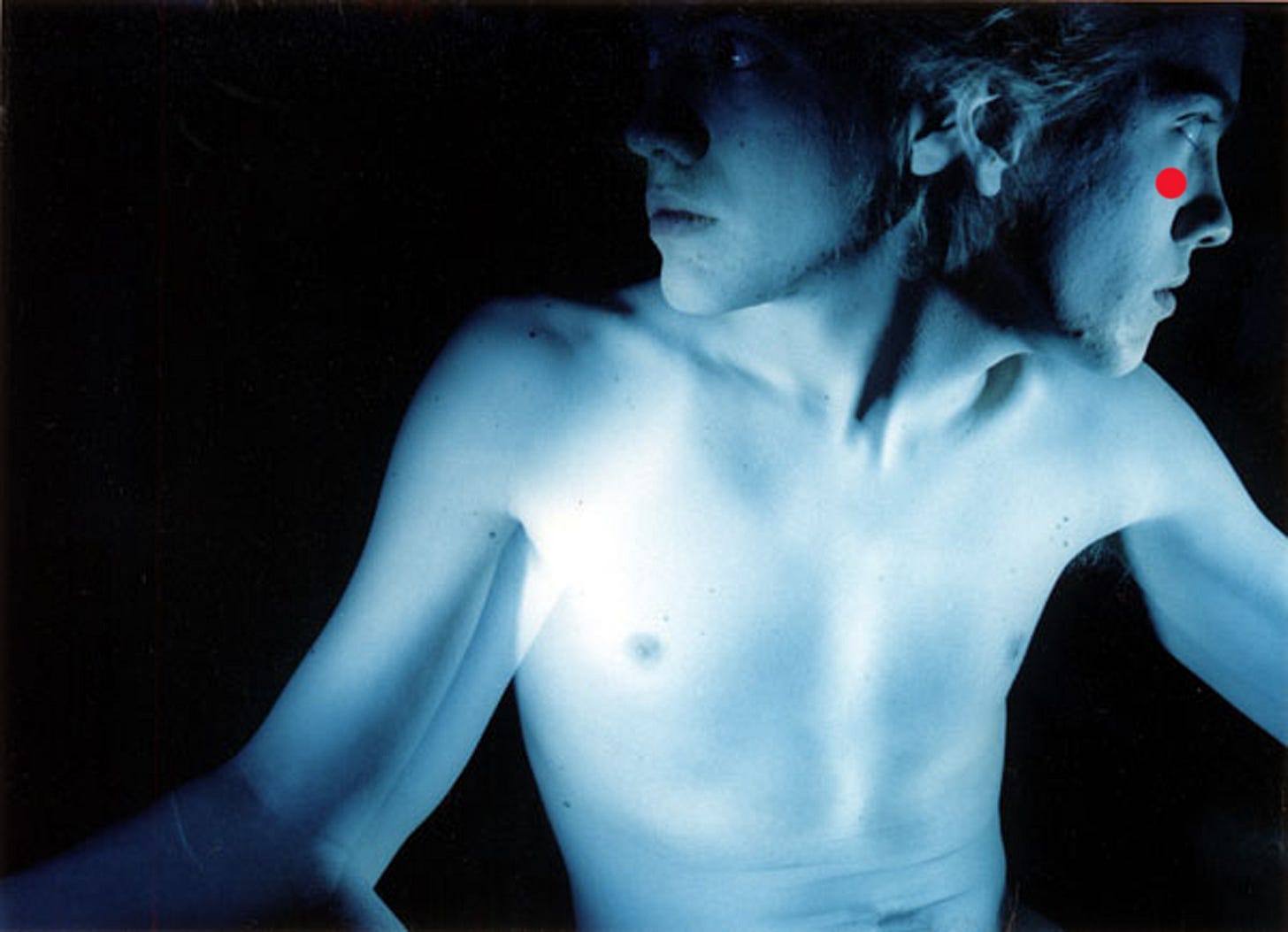

It's an easy, though apt, observation that Anderson's singing voice — a thin, reedy trill — sounds as if its owner is in pain. The guy looks kind of sickly, too, with a pale complexion and those thick glasses, through which his eyes seem a little out of proportion. But old pictures of him reveal an attractive young man, with piercing brown eyes and a strong jaw, and it is this guy who talks to you when you ask about his music, his band, or his health.

In March 2004, Anderson went into the hospital. Surely he saw it coming. During the previous year he had been living with Weisman in Oakland. When that relationship ended, he went a little nuts. He moved back in with his parents in Fremont, threw away all of his medication, and tried to subsist on a diet of raw food, meditation, and yoga classes at the Sacred Space Healing Center on Haight Street, a regimen that lasted approximately one month before his parents had to drag him to the hospital: “My dad told me after I got out that when they first left me that first night, he thought I might not make it through the night.”

His dad wasn't the only one.

“I got a call from him in the hospital, and he had gone down to 98 pounds,” remembers Cory Brown, who runs Absolutely Kosher, the label that's releasing High Road and Low Road. “I think he was seriously concerned that he wasn't going to see the records' release.”

Anderson, it turns out, is among the most prolific songwriters I've ever met. By his estimation he has written between 200 and 250 songs (prior to Dilute he wrote as Jacques Kopstein and was also one-half of Howard Hello). As he explains in what I'm sure is not meant to be a pun, “Writing songs [for me] is like shitting. How many times did you shit this week?”

In the year before he went into the hospital, in addition to playing guitar with Dilute and managing his flailing relationship and his sickness, Anderson was writing the material that would make up High Road and Low Road. When Brown received the phone call in spring 2004, he was expecting to release the more or less completed records once Anderson had made a few minor postproduction tweaks. (And while we're talking about production: Many of the songs on these albums consist of 200 tracks of sounds, which is so mind numbing that I won't even dwell on it.) [page]

But when Anderson got out of the hospital in May, he was in the worst shape he'd ever been in. This was when he got started on the IV. For months, he says, he was “not even recording. Jay would come by usually once a week, but our hangout sessions would be me laying in bed and him sitting in a chair, 'cause my anemia was so bad, my blood cell count was so low, I had no energy. For, like, a long time.”

In September 2004, he was finally able to put the finishing touches on the Okay records, and Brown was able to move forward with releasing them. Then, in January, Anderson got sick again. For a week he couldn't keep anything down, not even water. When he was admitted to the hospital the doctors told him his white blood cell count had fallen dangerously low. They feared it was leukemia. Anderson feared it was the end.

“There was a whole day and into the night when I thought, 'OK, this could be it.' And it's like, 'What have I done, what could have I done?' Just thinking of stuff like that.”

He made it through that night, but the next turned out to be even worse.

“I basically had 16 hours straight of just throbbing pain at the base of my spine. … The nurses were freaking out because they kept giving me morphine, but it didn't stop the pain. I was shaking, I couldn't lay in bed, I couldn't walk, I couldn't stand, I was just moving around. Not a fun night. But then it just went away. I couldn't sleep all night, and finally I passed out, and I woke up 20 minutes later and was fine.”

Anderson thinks that what happened to him was something called a “Kundalini Release.” The term “Kundalini” derives from a Sanskrit word that means “coiled up.” Dictionary.com defines it as “Energy that lies dormant at the base of the spine until it is activated.” A release is, well, apparently what happened to Anderson; he believes that this energy exploded out of him, kicking off a new kind of healing process and imbuing him with a heretofore nonexistent vigor, determination, and compassion.

You can raise your eyebrows if you like, but these are the facts: Okay played its first show on Feb. 23, 2005, at Noise Pop, a scant month after Anderson got out of the hospital the second time; the man plays in a band with his ex-girlfriend and the guy she cheated on him with, who is now her fiance; despite ongoing maintenance like the IV and the prednisone, etc., he is arguably as close as he's been in a long time to controlling the disease that has so relentlessly controlled him for the last decade. “It's like a fire has been lit,” he tells me.

The Very Brief Tale of the Bizarre Love Triangle

Kamps: Anna, could you please briefly tell me about the Bizarre Love Triangle?

Weisman: Yes. [Though not briefly. The 1,400 insightful and compelling words that Weisman and Lewis wrote on this subject could not fit in this space. Here are two representative paragraphs:]

“Anna and Marty moved to Lake Merritt in February 2003, whence Marty began recording the low/high road. Yosef went to Spain. While he was there, Anna told Marty that she had taken ecstasy with Yosef in 1999. Marty didn't want Anna to see Yosef anymore. Yosef was hurt and wrote a catchy song about it.”

[More things happen. Weisman and Lewis eventually end up engaged ….]

“Anna waited to tell Marty until he asked in January 2005. Marty took the high road. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Marty asked Anna to play in his new band in February. Marty and Yosef talked for the first time in two years and got on famously. Marty asked Yosef to play in the band. Marty, Yosef, and Anna are all waiting to see what happens now.”

The True Meaning of Pop

The show tonight in Oakland is at an art gallery/performance venue called Lobot. The various pieces adorning this cavernous industrial warehouse include an installation covering the south wall featuring dozens of X-rays of lungs; a selection of paintings, among them one hung above the bathrooms of a girl sitting on the toilet; a really bright green neon sign hung 15 feet up the north wall, the one just behind the stage, which flashes a message every few seconds, bright enough to tint green the whole of the cathedrallike space: “You Will Die Someday.”

It's 12:30 a.m. when Okay arrives onstage, the last act on a four-band bill. As the assembled audience members take their seats on the floor and on what happen to be actual wooden pews, the show begins, as it always does, with Tingshas, which ring crisp and tinny, a thin percussive layer of high-frequency Xanax. Warm keyboards ooze up, and strummed guitars set the pace. The song is called “Adi Mantra”; Anderson sings, in his quavering, effected voice, “I've been waaaasting so much tiiime.” The music swells, keyboard sounds double up on each other, and a cymbal slithers out above the din.

The green neon sign blinks: You Will Die Someday.

Bang. Bang. Bang.

The musicians fire their cap guns at one another, which gets a laugh, communicating that yes, this shit is spiritual and important, but no, we're not taking ourselves too seriously. Next song: “Bloody,” a perfectly deranged pop ditty. Anderson's keyboards are all cute and cuddly, emitting syncopated chords as he sings, “Bloody bloody/ Our way is going to be the way/ Bloody bloody/ We don't ask why.” Then the tune explodes — literally, because before the show Lewis handed out little exploding party-poppers to select audience members, so that when Jay Pelucci slams his cymbals and Panda bangs whatever she bangs and Anderson yells, “OUT!/ Of our way,” bursts of confetti spill from various corners of the room, and the music turns into something like a lost Ringo-penned Beatles tune, romping and stomping, before everything drops out and it's just Anderson singing over a vaudevillian keyboard line, “You're gonna die but how/ You're still alive right now/ You're still alive right now/ What to do?” Then the band joins in and it's Ringo's romper room again, and the party builds and builds — like weather, I tell you! — and then stops. [page]

And the green neon sign blinks: You Will Die Someday.

The song ends and there's a moment of silence, about a minute's worth (which is sort of awkward for the audience, to tell you the truth), and the silence is broken by the musicians pulling out those things that look like kazoos and blowing in unison a loud, squeaky fart. For “Wild West” a few songs later, after Anderson sings the refrain — “We're not headed for disaster” — and the song ho-hums its way into a sashay of keyboards, Weisman and Panda punctuate the sound with the wheezy, percussive chirps of deflating balloons.

Maybe this scene sounds cheeky and twee, but the kazoos and the balloons and the cap guns are all necessary, because something needs to lift this zeppelin off the ground, because when Anderson sings, on High Road's “Compass,” “I consume all the sadness/ That you throw over me/ And I spin like a compass/ That don't know where you be,” he's singing a song he wrote when the girl sitting behind him was tearing his heart out by sleeping with the guy standing to his right — and somehow he's forgiven them both. Which is some heavy shit. And when he sings, on “Give Up,” “I'm gonna give up/ I've got to give up/ And on you go,” and it's not really clear which towel he's talking about throwing in — his life? his relationship? — well, that's some heavy shit, too. But it's cool, Anderson wants us to know. Maybe that's why he closes out the show with “Sing Along,” a snappy kazoo-laden tune that bounces around your head like a pingpong ball: “It's all right it's such a sad, sad fucking song/ It's all right if you're still singing along.”

You Will Die Someday. It's not a warning or a threat, merely a reminder.